NASCIO Contacts & Primary Authors: Doug Robinson, Executive Director and Meredith Ward, Deputy Executive Director

Table of Contents

Executive Summary | Generative Artificial Intelligence | Digital Services | Enterprise Architecture | Business Continuity / Disaster Recovery / Resiliency | Business Operating Models | Acquisition | Workforce | Identity and Access Management | Federal Cybersecurity Spending | Conclusion

Executive Summary

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! (Yes, really!) That’s right, it’s NASCIO State CIO Survey time! We conducted the survey in the summer of 2024 and had 49 state chief information officer (CIO) responses to questions on nine topics and we also conducted a few CIO interviews on those topics. In the years since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have written a lot about issues that have come at state CIOs like a 100-mile-per-hour pitch from the mound: generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), digital government services, workforce and, of course, cybersecurity. This year’s survey is no different where we asked about many of those issues as well as some fundamentals.

For example, it seems that consolidation and centralization aren’t going anywhere soon with CIOs reporting that they are delivering services to agencies by consolidation of infrastructure, consolidation of services and centralization of IT (information technology) project management. We also asked questions about the fundamentals of state technology organizations like enterprise architecture (EA), acquisition (how do we define a technology procurement?), disaster recovery and workforce. We’ve learned that there’s much ground yet to be covered within EA and state CIOs are fighting tooth and nail to attract and maintain a qualified workforce (hint: do not abandon diversity and inclusion while doing so).

But, of course, we could not get away from GenAI as it seems no technology conversation these days does. In the 2023 NASCIO State CIO Survey we wrote about GenAI and its debut on the state technology scene. This year we asked a few questions about how state CIOs have approached GenAI and, to be expected, they have set up task forces, created policies and implemented acceptable use policies.

There’s also some good news on the identity and access management (IAM) front—both internal and citizen facing. IAM is one of those issues that was thrown like a fast pitch to CIOs, and they have responded in kind. The demand for citizen-facing IAM can be attributed to the increased demand for digital government services. While there’s still work to do, much progress has been made on IAM.

We believe this year’s survey is fairly indicative that state CIOs are focusing on the fundamentals, e.g. the building blocks of state technology. This groundwork will undoubtedly pave the way for the next generation of state CIO offices in 2025 and beyond.

Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) continues to change how the world lives and works. It is especially important to state CIOs and their citizens, ranking at number three in the 2024 State CIO Top 10 priorities list. Recent NASCIO publications explore current and potential use cases leveraging GenAI to improve efforts like accessibility, digital citizen services and workforce efficiency. As GenAI is still in its early stages, we have a unique opportunity to learn from its current state and prepare for the future. In this year’s CIO survey, we asked state CIOs to detail their experiences regarding GenAI in their current practices, state laws and GenAI tool use.

We asked CIOs which action items regarding GenAI have been implemented in their states. Over 60 percent of respondents indicated that at least one of the following GenAI practices has been implemented:

- The creation of advisory committees and task forces (78%)

- Implementing enterprise policies and procedures on development/use (72%)

- Responsible use / flexible guardrails / security / ethics (67%)

- Inventory / documenting uses in agencies and applications (61%)

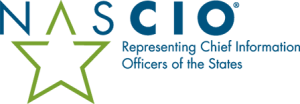

When asked if employees in the CIO’s organization use GenAI tools in their daily work, 53 percent of participants said yes while 29 percent said no. Six percent of respondents were unsure. One CIO told us that AI is “mostly” used in document creation, but their state is “quickly moving into RPA.” Another state CIO said they are using “public tools in a basic fashion [without] involving any sensitive information.”

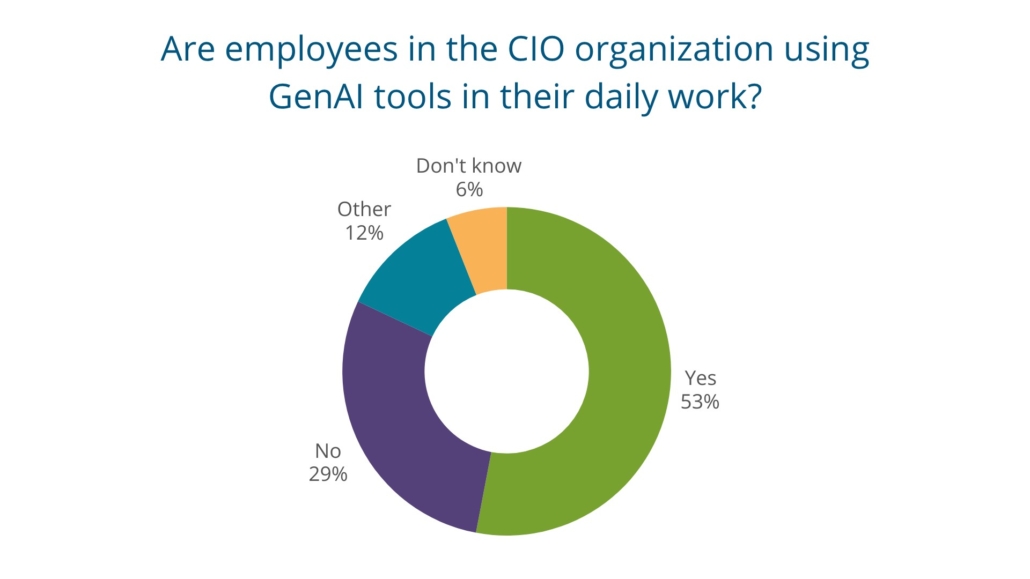

We also asked what types of AI tools are being used by state executive branches. Sixty-five percent are using free online tools and 60 percent are using commercial-off-the-shelf tools. One CIO also told us, “Tools being utilized have or are being integrated into existing enterprise solutions.”

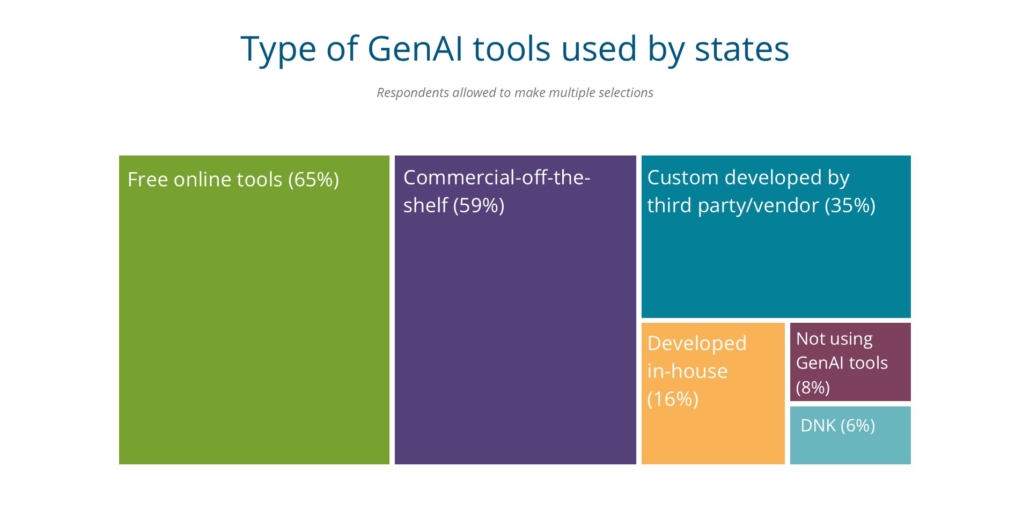

Next, we asked CIOs if their states currently use GenAI in certain business practices. The top GenAI business practice use cases are virtual meeting assistants and transcription; cybersecurity operations; document generation and management; and software code generation. The top business practices

where GenAI is being piloted include document generation and management; data analytics / predictive analytics; virtual meeting assistants and transcription; and software code generation.

While GenAI holds a lot of promise for the future of state government IT, it’s clear from our survey data that most states are still in the early phase of adoption and are taking a cautious approach. We know from previous research on AI that challenges to AI adoption such as poor data quality, lack of AI

governance and a workforce skills gap are still roadblocks to utilizing the full potential of AI.

Digital Services

In the last four years, state digital government services have seen both rapid developments and consistent trends. For example, the 2020 and 2021 State CIO Surveys examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and citizen demand as a driver for digital services. In the 2022 State CIO Survey, states and state CIO organizations reported moving fast to embrace digital transformation and technology modernization.

In this year’s survey we asked about major challenges states are facing in meeting the demand for digital services and the top three challenges are:

- Lack of adequate funding and budget to balance immediate public needs with future critical investment.

- Data and information quality requirements and digitization complexity restraints.

- Workforce skills and capability constraints to deliver/implement digital services.

Interestingly, when we asked the same question in 2022, the top three responses were workforce skills and capability constraints to deliver/implement digital services (#3 in 2024); lack of organizational agility/ flexibility (#5 in 2024); and lack of adequate funding and budget to balance immediate public needs with future critical investment (#1 in 2024).

While demand for digital government services has increased, budgets have not kept up with the demand. As one CIO told us, “The biggest constraint here is that digital delivery extends beyond current organizational and financial control boundaries. We struggle with sustaining services like this.” And budgets are not the only barrier as many CIOs told us that agency silos remain an inhibitor to progress. One state CIO said, “Our agencies are hesitant to assist IT with citizen digital experience because they are more interested in how they process work internally.”

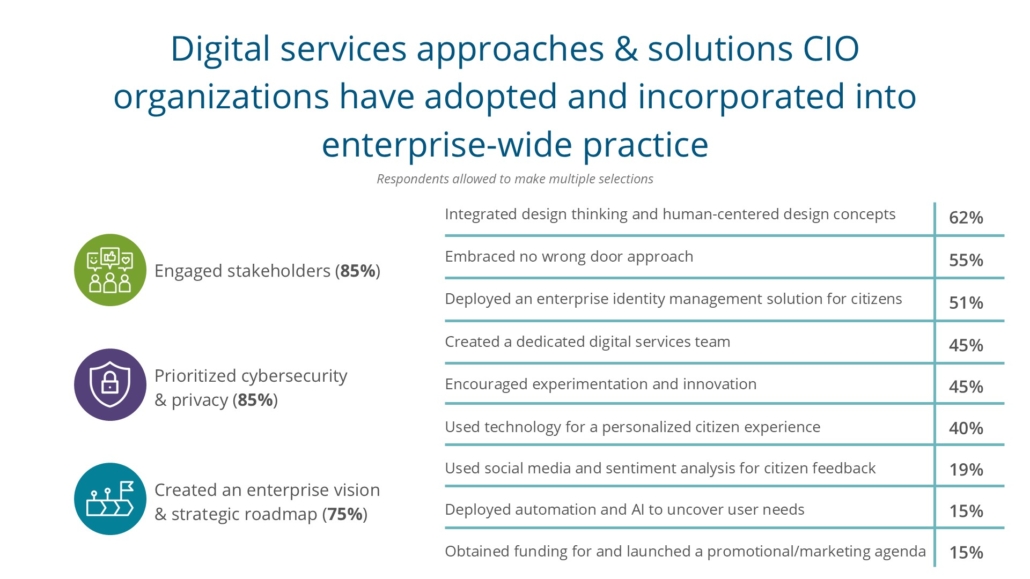

Next, we asked about digital services approaches and solutions adopted by the CIO organization and incorporated into enterprise-wide practice. The top responses are engaged stakeholders (e.g. agencies, citizens and others); prioritized cybersecurity and privacy; and created an enterprise vision and strategic roadmap. Interestingly, 45 percent of states have created a digital services team, up a bit from 41 percent when we asked a similar question in 2022. Additionally, only 15 percent of states deployed automation and AI to uncover user needs in 2024, down from 20 percent in 2022.

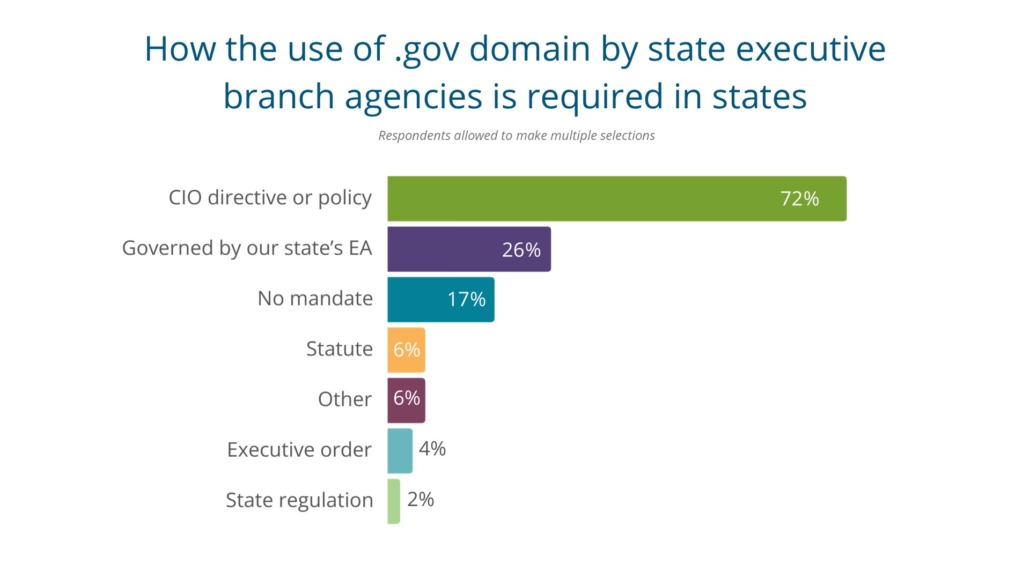

One critical issue under the digital government (and cybersecurity) umbrella is adoption of the .gov domain; an issue that has been a top NASCIO federal advocacy priority for several years. While the .gov domain provides enhanced security features and increases the public trust in government, most local

governments are not registered on the domain. However, the majority of states have adopted .gov in all or part of executive agency websites. An overwhelming majority of states indicated that .gov domain use is mandated by a CIO directive or policy. Other methods of requirement include incorporation into the state’s enterprise architecture (26 percent), statute (six percent) and executive order (4 percent).

Unsurprisingly, a few CIOs told us that the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program has improved local government, judicial and legislative adoption of .gov. Next, we asked a few open-ended questions about measuring success in digital services and innovation in the digital government journey. Some states don’t have a formal or holistic approach in place yet to measure the success of digital government services but are working towards it. Still others are measuring digital vs. in person services usage by citizens. Many states are focusing on human-centered design and surveying public users to gauge satisfaction. As one CIO told us, “We are implementing a solution that successfully meets stakeholder needs and is intuitive to use by anyone.” And another CIO told us they established a central citizen engagement team. Finally, one CIO shared that their efforts are directly supported by their governor, and they have developed a digital maturity scorecard. Finally in this section we asked CIOs to highlight any recent innovations in their state’s citizen-facing digital services journey and a few are listed below:

- Launching domain specific content for business, jobs, healthcare and others to create a more holistic approach.

- Rolling out identity and access management to over one million constituents.

- Establishing a multimillion-dollar technology modernization fund to improve customer experience with digital services, reduce risk and support more efficient delivery of government services.

- Redesigning all state websites incorporating new digital experience principles as well as a common look and feel.

- Launching a new accessibility webpage designed to improve access to government services for citizens with disabilities.

- Establishing a secure, single front door for the user communities when interacting with state services which serves as the backbone of the state’s digital infrastructure, facilitating streamlined interactions and improving overall user experience.

- Tying the state’s citizen portal project to data privacy so that citizens are able to see what data the state has, and the privacy rules associated with it.

One state told us that, aside from artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, digital transformation and citizen experience have been the areas getting the most attention. While this is certainly welcome news and we hope that attention spreads to all states, there is still work to be done. In NASCIO’s 2023 publication, Creating A Citizen Centric Digital Experience: How Far Have We Come?, we wrote, “The citizen experience should no longer be about individual department services. There are strong collaborative relationships that are necessary and present to support these departments.” In that publication we also issued some calls to action that are still very much applicable:

- Create an enterprise vision and strategic roadmap

- Engage stakeholders

- Prioritize cybersecurity, privacy and identity management

- Embrace no wrong door

- Create a promotional agenda

- Look toward the future

While there has been much emphasis on digital government services in the past four years, more work lies ahead. The vision is that any service citizens can complete in a state building can be done online. Challenges may persist, but state CIOs are heavily focused on that vision.

Enterprise Architecture

Past state CIO surveys have surfaced patterns of success regarding the power and the value of a formal enterprise architecture (EA) program. However, this is the first year in which NASCIO officially addressed enterprise architecture as a topic to be included in the state CIO survey. The evolution of EA has progressed from some states integrating data architecture within an overall enterprise architecture to a strong recommendation to leverage enterprise architecture for improved IT procurement. In the 2019 State CIO Survey there was a focus on the emerging role of the state CIO as a broker of services as “Next Generation Enterprise Architecture” surfaced in the top five skills and roles needed as part of the business model for the state CIO organization. Additionally, NASCIO has published significantly on this topic through the years including the creation of a comprehensive enterprise architecture toolkit that includes governance, business architecture and other essential aspects of enterprise architecture.

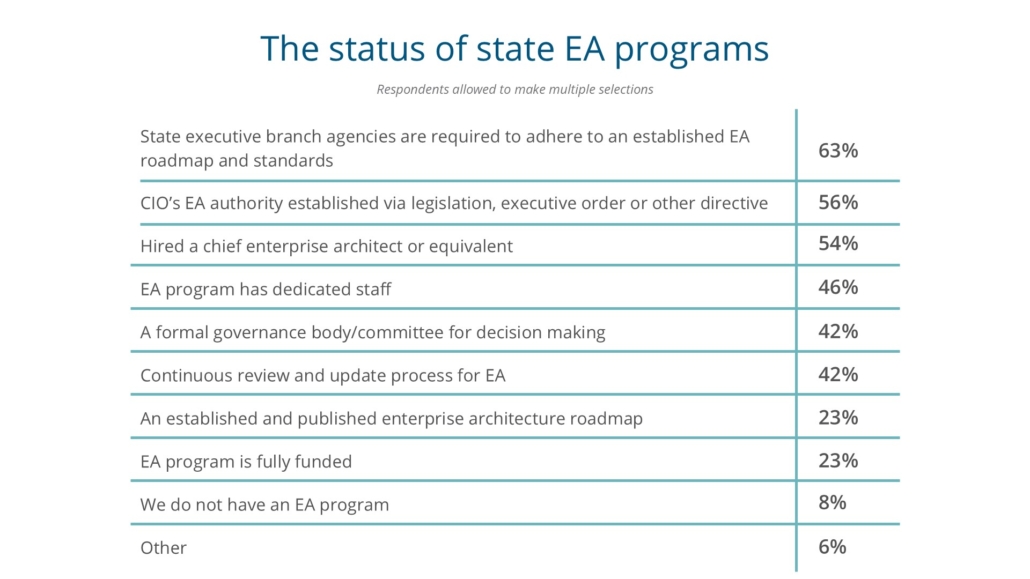

On this year’s State CIO Survey, we asked state CIOs for an assessment of their enterprise architecture program. Impressively, 64 percent of respondents require agencies to adhere to an established roadmap and standards. Additionally, the authority for EA is clearly established in 56 percent of the states. A similar percentage of respondents (54%) report the presence of the chief enterprise architecture role.

Nearly half of respondents report having a dedicated staff and a formal governance body—a critical element of EA that not only helps to ensure application of adopted standards but brings in the essential participation from agency business leaders in the process. Their authority, participation and support can help establish enterprise-wide adoption. While there is still much progress to be made, it is encouraging to see these signs of advancement.

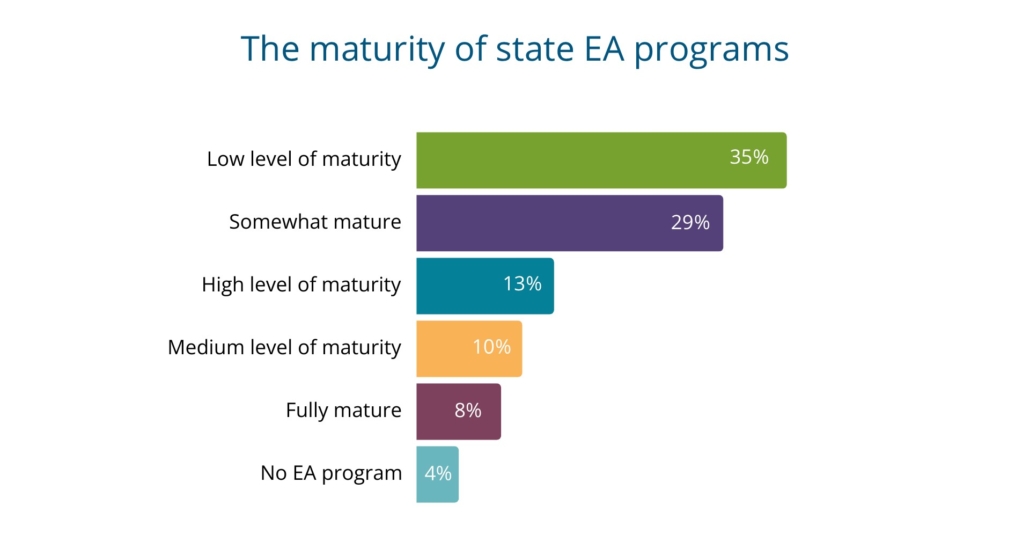

Next, we asked state CIOs to assess the general maturity of their enterprise architecture programs. About one-third of respondents report a low level of maturity (35 percent) and around another third of states report they are somewhat mature (30 percent). A minority (13 percent) of state CIOs assessed

their state as highly mature in their enterprise architecture program. The encouraging news is that most states have an enterprise architecture program, and a very small minority (4 percent) have no enterprise architecture program.

The enterprise architecture discipline will continue to evolve and mature and NASCIO has been using the term “next generation enterprise architecture” in conversations across the states. NextGen EA is a necessary capability for enabling the emerging state CIO operating model, aka, CIO as broker. We anticipated and received some corroboration that a significant part of future emphasis will be on business architecture with one CIO saying, “We recently restructured the [EA] team and have a specific focus on growing the business architecture team. It has been challenging to find resources.”

The state CIO operating model is continuing to evolve with significantly less internal development and more “as-a-service” cloud initiatives and implementations. This approach has an impact on state government enterprise architecture principles and standards which now must be present in things like contracts versus only in an internal development project discipline. Enterprise architecture and its various component architectures must be leveraged to reduce complexity and variety, and standards are equally important whether states are developing internally or engaging external providers. That is why we asked about how EA integrates into the technology procurement process. The majority of respondents report that their enterprise architecture team has influence with procurements.

We also asked state CIOs to describe what data, information and tools they are using to justify IT-related investment decisions. The responses present a wide spectrum of approaches, some of which are rather advanced. For instance, several states are using sophisticated EA platforms that provide advanced capabilities for documenting, analyzing and reporting. States are employing effective discipline related to inventories and portfolios that include assessments of the health of investments and projects. Some states report evaluating incoming investment requests against enterprise architecture principles and standards for security, consistency, resiliency and cost-effectiveness.

Some states also report active use of various external references such as technology business management, FedRAMP, StateRAMP and the National Information Assurance Partnership (NIAP) for evaluating strength and viability of investment requests. States are also focusing on carefully evaluating investments in hardware, software and professional services by establishing requirements, negotiating contracts, providing needed assistance in writing effective business cases and conducting economic evaluations that carefully look at the promised value of demand-based investments.

States are making progress toward effective and mature governance and enterprise architecture as the field of enterprise architecture itself is changing and maturing. Still, in our interviews with CIOs some told us that EA is understood but not widely used in agencies. Some also said it isn’t understood at all beyond the CIO’s office. Despite this, CIOs are moving forward with one CIO telling us “I have worked to secure stronger buy-in for a greater enterprise strategy.”

Enterprise architecture is not tied to any one project but provides for the orchestration of the entire project and IT investment portfolios. EA will be more important going forward as states are addressing such critical challenges as identity and access management, digital government and services, cloud services and emerging technologies.

Business Continuity / Disaster Recovery / Resiliency

After living through the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing cybersecurity attacks and various natural disasters, CIOs are thinking more about what it means to be resilient when facing and recovering from disasters.

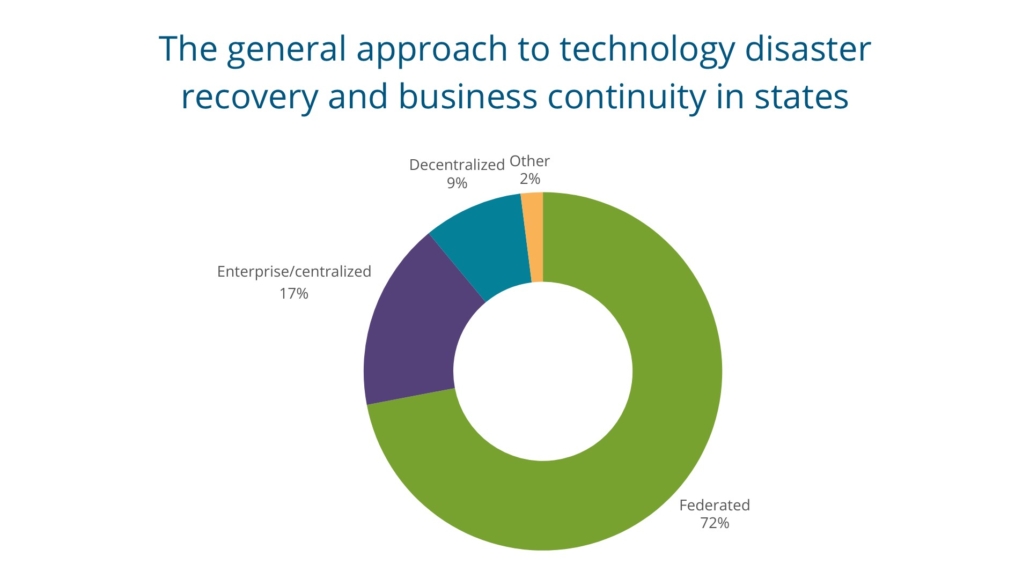

We wanted to know generally if the approach to disaster recovery and business continuity (DR/BC) in the states is characterized as enterprise/centralized (the CIO or CIO-directed third party delivers all DR/ BC services), decentralized (agencies are responsible for their own DR/BC) or federated (a mix of agency and CIO organization responsibility). The most common answer was the federated model with 72 percent of CIOs choosing this option, followed by enterprise/centralized at 17 percent and decentralized at nine percent. When we asked this question in 2020 only 61 percent of states had a federated model. Many respondents highlighted the nuances of the individual state approaches and mentioned that while the CIO may have a general overall responsibility, agencies are often responsible for certain aspects of the process or decisions.

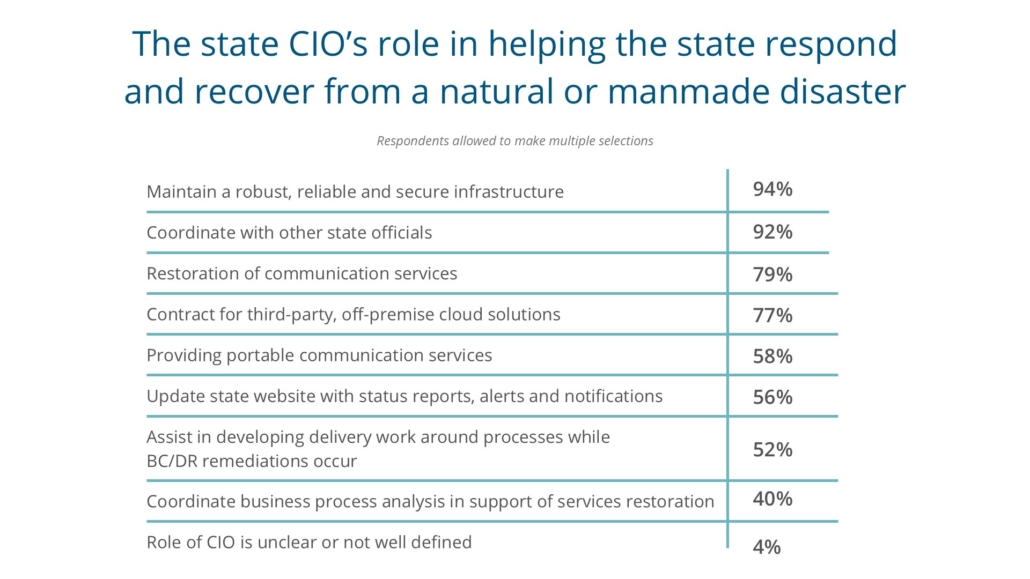

State CIOs hold several key roles in helping their states recover from a natural or manmade disaster.

The four most common are:

• Maintaining a robust, reliable and secure infrastructure (94 percent);

• Coordinating with other state officials (92 percent);

• Restoring communication services (79 percent); and

• Contracting third-party, off-premise cloud solutions (77 percent).

These top three roles are the same as they were in 2020 when we last asked the question. As one CIO said, “Maintaining the network is one of the most key responsibilities.”

CIOs continue to see their role as focused on continuity of operations as opposed to provision of new or enhanced services while states recover from a disaster or disruption in business services.

Business Operating Models

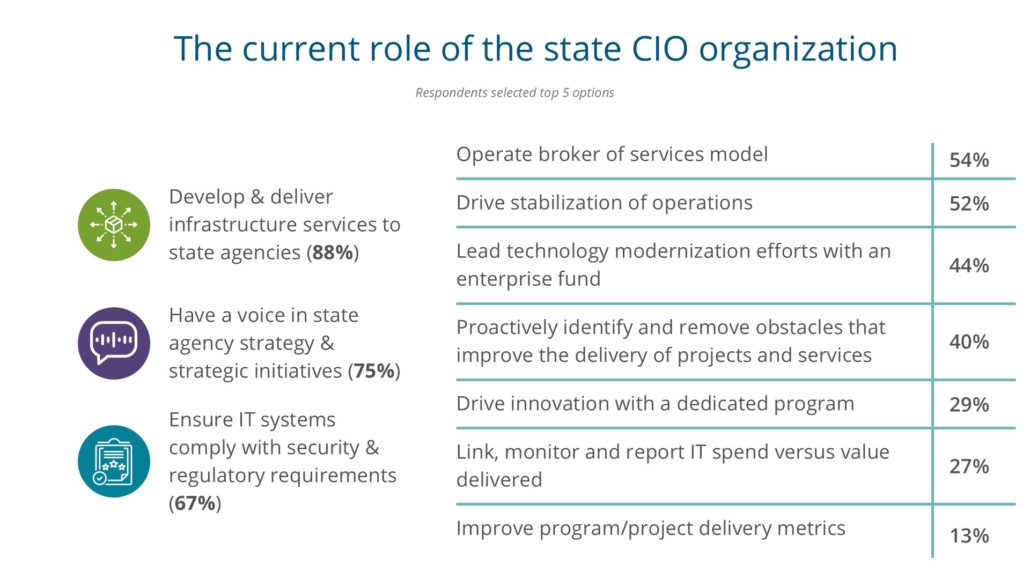

One trend that we have seen consistently in the last decade of surveys and our other research is that consolidation and centralization continue to be a big theme in state CIO offices. The cost savings, reduced risks and streamlined benefits to states cannot be understated. But, before we delve into how CIOs are delivering services, we need to talk about how state CIOs perceive the role of their organization.

We asked how CIOs would describe the current role of the state CIO organization and allowed them to choose their top five responses. In the 2022 State CIO Survey we asked the same question and CIOs also chose these as their top three, but in a different order. The top three aggregate responses and how they compare with the 2022 survey are:

- Develop and deliver infrastructure services to state agencies (#2 in 2022)

- Have a voice in state agency strategy and strategic initiatives (#1 in 2022)

- Ensure IT systems comply with security and regulatory requirements (#3 in 2022)

Interestingly, “operate a broker of services model” came in at number four this year, beating out “drive innovation with a dedicated program,” which moved way down to number eight in this year’s survey (it was number four in 2022). Although these responses reinforce the “traditional” CIO operating model, we also see growing evidence of CIO organizations expanding their role and portfolio.

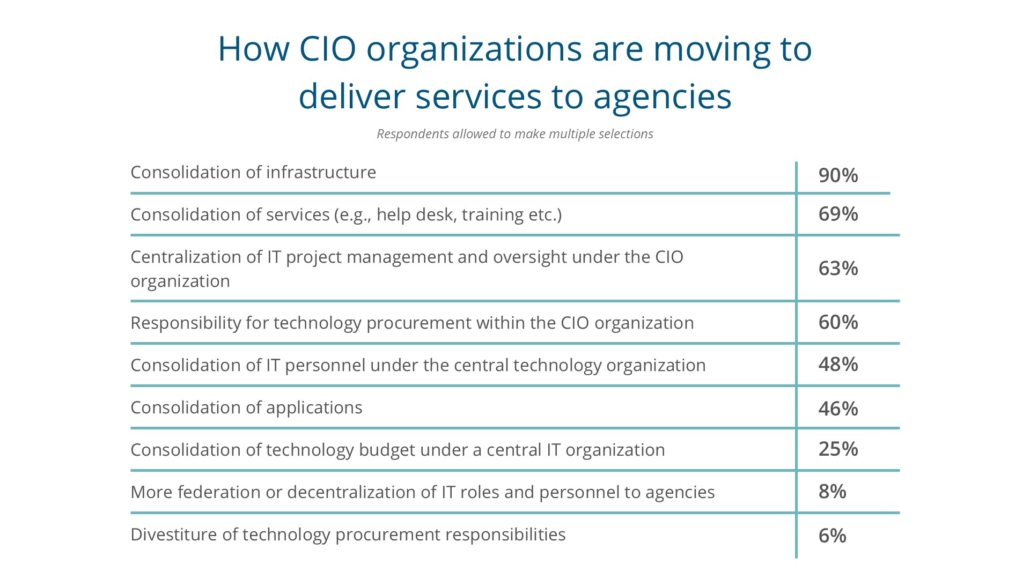

As stated earlier, consolidation and centralization continue to be a big theme in state CIO offices from infrastructure to applications to personnel to responsibility for project management or IT procurement. In this year’s survey we asked state CIOs how their organization is moving to deliver services to agencies, and they were allowed to select all that apply. Just as they were in 2022 when we last asked, the top three

responses are:

Consolidation of infrastructure (#1 in 2022)

• Consolidation of services (#3 in 2022)

• Centralization of IT project management and oversight under the CIO organization (#2 in 2022)

Options that didn’t make the top three still follow the same theme of consolidation of personnel, applications and budgets. One CIO told us that “IT personnel consolidation is directly related to consolidation of services and infrastructure.”

CIOs told us of further consolidation plans that are backed by policy, legislation or executive order. The motivations for consolidation continue to be legacy modernization, cost savings and cybersecurity. Still, not every state will be consolidated but might consolidate services. As one CIO told us, “While we still operate in a federated model, we are transitioning agencies to shared services at an unprecedented rate. It is also noteworthy that we maintain statewide tooling for security monitoring and response.”

And, finally, what if a CIO agency is already consolidated? What is the next step? One CIO said, “We’ve consolidated but the next phase is to expand into more direct support for agencies.” We expect consolidation and centralization to continue to evolve in the coming years.

Acquisition

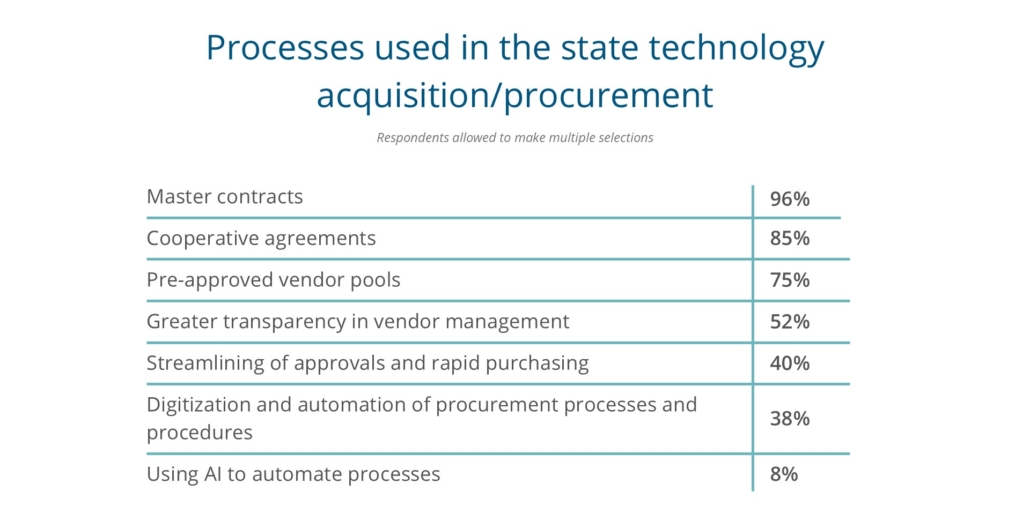

The acquisition process—of which procurement is one part—is an issue that NASCIO has covered for several years, last asking about the topic in-depth in the 2019 State CIO Survey. However, during the 2021 State CIO Survey, we asked CIOs about procurement processes put in place during the pandemic/ emergency orders that may be retained, and many told us the following would have a lasting impact on the acquisition process moving forward:

- Pre-approved vendor pools

- Master contracts

- Increased use of cooperative agreements

- Digitization and automation of procurement processes and procedures

- Streamlining of approvals and rapid purchasing

- Greater transparency in vendor management

Fast forward three years and we asked CIOs in this year’s survey what processes states are using in technology acquisition/procurement, almost 96 percent of CIOs indicated use of master contracts. The next three top responses were cooperative agreements, pre-approved vendor pools and increased transparency in vendor management.

Next, we asked state CIOs something that we have thought a lot about here at NASCIO over the last several months: how to define a technology acquisition/procurement. Simply put, this is not an easy task. As one CIO said, “Struggling with the question (still). Primarily focused on a procurement that PRIMARILY serves a technical purpose versus other purposes.” Other CIOs told us this definition is very broad in their states, not very well defined or using out of date terminology.

Next, we asked state CIOs something that we have thought a lot about here at NASCIO over the last several months: how to define a technology acquisition/procurement. Simply put, this is not an easy task. As one CIO said, “Struggling with the question (still). Primarily focused on a procurement that PRIMARILY serves a technical purpose versus other purposes.” Other CIOs told us this definition is very broad in their states, not very well defined or using out of date terminology.

“No formal definition exists. We know it when we see it.”

“[This is] becoming more blurred as technology underpins so many business processes. If a tech component or software agreement is required, it becomes an IT procurement.”

Still, overall, most CIOs stated a technology procurement is any procurement of a technological service or good including but not limited to hardware, software, cloud technologies and data security technologies. So, if it walks like a technology procurement and quacks like a technology procurement, it might be a technology procurement.

CIOs were then asked if their states use AI in the acquisition process, and, if so, how. Most states indicated that they were not using AI during acquisitions at this time or were exploring its use. We also asked CIOs about potential use cases for AI in their state’s acquisition process.

Common themes among these responses include request for proposal (RFP) and request for information drafting/evaluation, contract review/analysis and data analysis. One state CIO told us that some state agencies are using chatbots internally to help answer purchasers’ questions about the procurement process.

Other potential use cases include:

- Automating and improving needs assessment, market analysis and proposal evaluation

- Identifying and assessing the best vendors

- RFP scoring

- Monitoring vendor performance and risk management

- Optimizing budgeting through spend analysis

- Contract management and optimization

One CIO told us that AI could, “Ensure transparency and accountability by providing real-time insights throughout the procurement process. Implementing AI could lead to more efficient, accurate and effective technology acquisitions for the state.” We also know from research done earlier this year with the National Association of State Procurement Officials (NASPO) and academic researchers from Boise State University and Florida International University that AI can aid procurement by enhanced decision-making, process automation, improved transparency and compliance and better vendor relationship and contract management.

Improving the state technology acquisition process is one that NASCIO has and will continue to advocate for. It is important to note that, in 2016, NASCIO issued five Recommendations for Improved State IT Procurement, and started a partnership with NASPO that continues today. Below are the recommendations we issued in 2016, and while there has been some progress on these, many states have yet to adopt them.

- Remove unlimited liability clauses in state terms and conditions

- Introduce more flexible terms and conditions

- Don’t require performance bonds from vendors

- Leverage enterprise architecture for improved IT procurement

- Improve the negotiations process

Workforce

Addressing issues regarding the technology workforce has been in NASCIO’s Top 10 for state CIOs for years, ranking at number five for 2024. Workforce encompasses preparing for the future workforce and reimagining the government workforce; transformation of knowledge, skills and experience; more defined roles for IT asset management; and business relationship management and service integration. NASCIO has a variety of publications discussing nuanced workforce issues – many of which were inspired by iterations of this survey over the years. In this year’s state CIO survey, we revisited workforce issues, focusing on recruitment, retention, goals and diversity efforts.

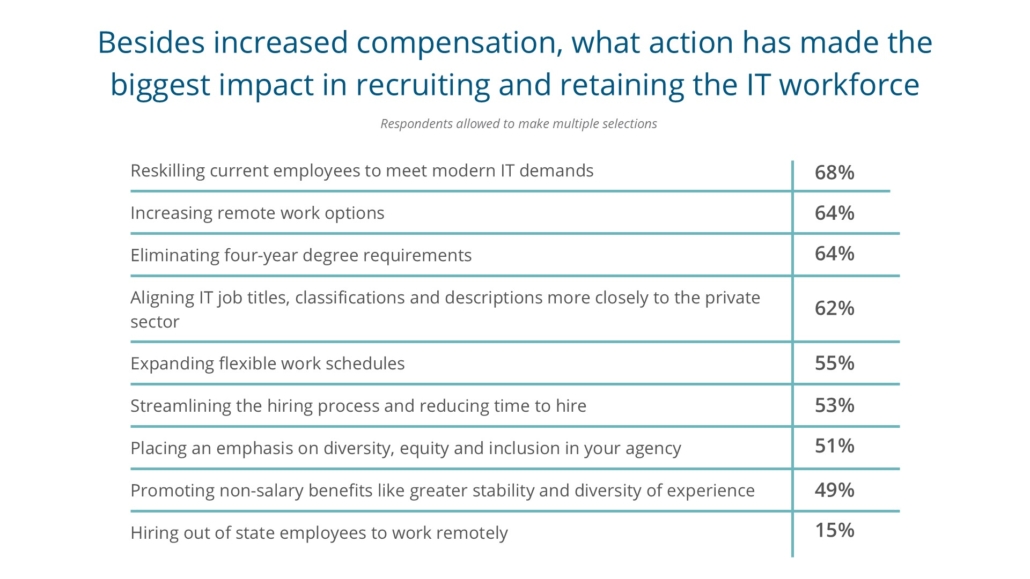

We asked CIOs, besides increased compensation, what actions their states have implemented that have been the most impactful in recruiting and retaining the technology workforce. Four implemented actions were indicated as most impactful by more than sixty percent of CIOs:

- Reskilling current employees to meet modern IT demands (68%)

- Increasing remote work options (64%)

- Eliminating four-year degree requirements for some roles (64%)

- Aligning IT job titles, classifications and descriptions more closely to the private sector (62%)

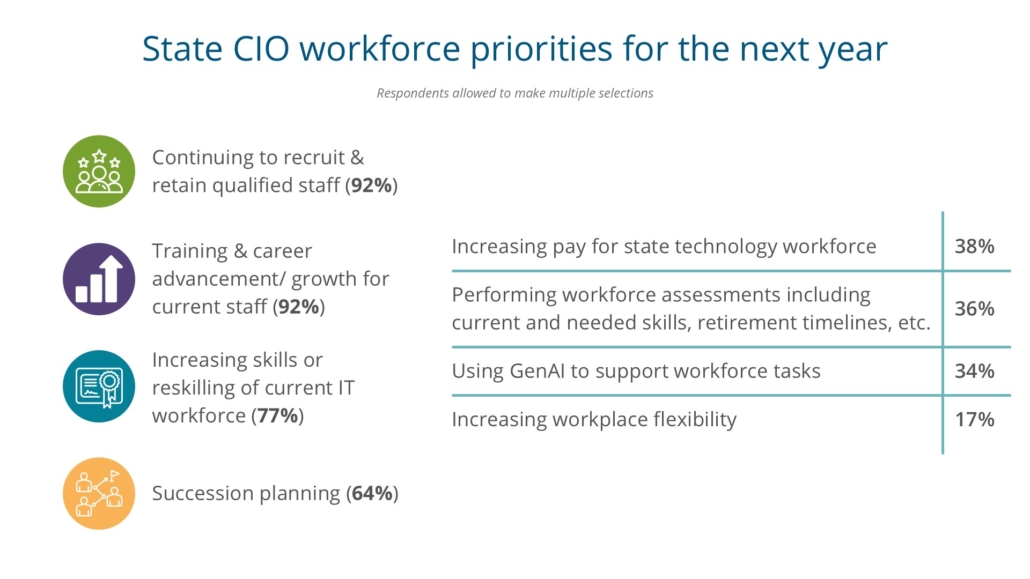

We also asked state CIOs about their workforce priorities for the next year. Ninety-three percent of participants indicated that continuing to recruit/retain qualified staff and training and career advancement/growth for current staff are priorities. Other shared CIO priorities include increasing skills

or reskilling of current technology workforce and succession planning.

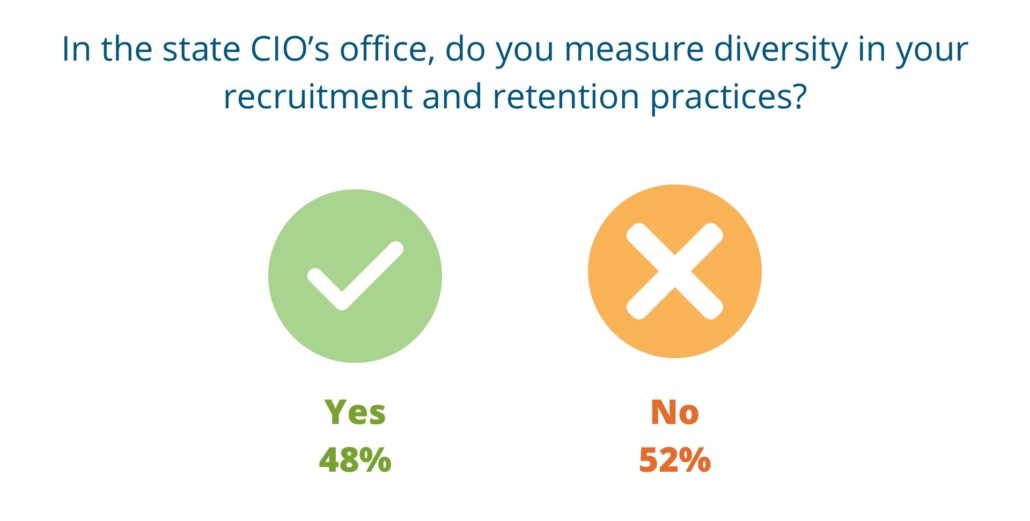

Next, we asked state CIOs questions about diversity in their workforces. When asked if diversity is measured in recruitment and retention practices at state CIO offices the responses were almost evenly split, with forty-eight percent of participants saying yes while fifty-two percent said no. This is in contrast to when we asked the same question in NASCIO’s 2022 publication, Diversity and Inclusion: An Essential Element to the State IT Workforce, 62 percent of CIOs said yes and 38 percent said no.

On this year’s survey we asked for open-ended responses to this question, and they revealed that, where diversity measurement occurs, it is in statewide practices and mandates, human resource-managed programs, cross-agency efforts and interagency teams dedicated to diversity practices. Open-ended

responses from state CIOs with no diversity measurement practices largely indicated other barriers such as statewide anti-DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) statutes and policies.

“We’ve created dashboards and have regular reporting on the diversity of our workforce including measuring and monitoring the percentage of women, BIPOC and individuals with disabilities we recruit and retain over a rolling two-year period. We’ve exceeded our goals in retaining the diversity we hire, and we do not have any underutilization in any of our [job classifications] (officials and administration, professionals, technicians, paraprofessionals and administrative support).”

“Overt DEI work will not fly at this time. We will hire any qualified candidate regardless of other considerations.”

“We have dedicated DEI staff and review our HR metrics bi-monthly. We alter our practices to improve diversity across levels and classifications.”

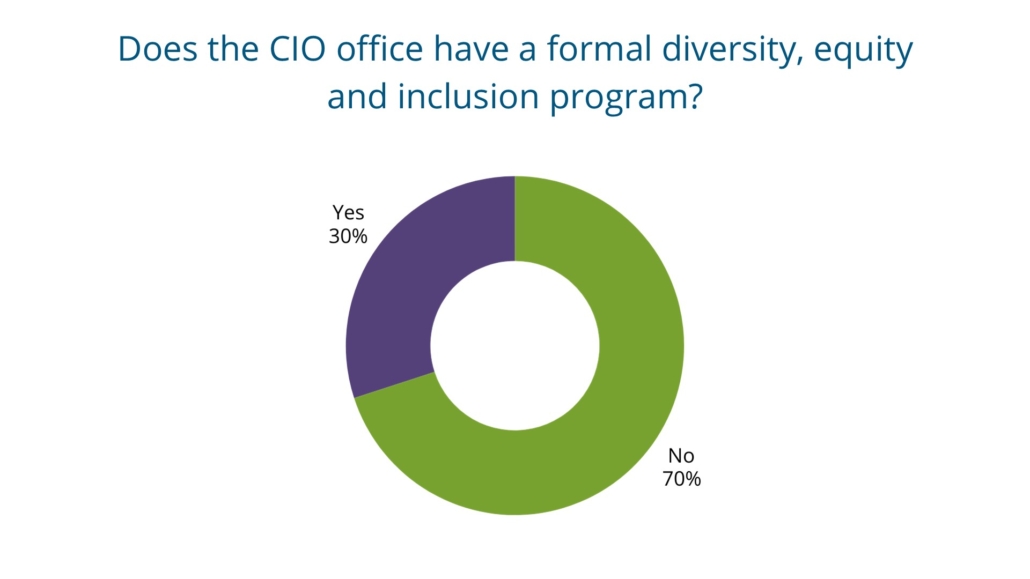

When asked if the state CIOs office has a formal diversity, equity and inclusion program, about thirty percent of CIO’s said yes while about seventy percent said no. Open-ended responses to this question among those who said no also cited statewide anti-DEI statutes and policies. Contrarily, some states participate in cross-agency/centralized programs that are also mandated by state governments. As diversity, equity and inclusion will remain prevalent across a wide range of workforce issues, state CIOs are encouraged to deepen their current practices using NASCIO recommendations seen in “Diversity and Inclusion: An Essential Element in the State IT Workforce.”

“In our state, there was an anti-DEI statute passed, as DEI was considered to have gone astray and become weaponized as a very negative tool of discrimination.”

“We have a team that focuses on diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility. They provide insight, recommend training and drive awareness in those areas.”

“[Our] program is a cross-agency staff-led effort targeting 39 objectives/actions to increase our DEI efforts. Some of those objectives include creating annual unconscious bias training, hosting monthly connected culture conversations on topics impacting employees to promote our connected culture,

making more visible the work of our agency to underrepresented populations, and implementing the use of an equity analysis tool in policy development and vendor selection.”

While state CIOs are fighting tooth and nail to recruit and retain a workforce for today and in the future, DEI is one thing that cannot be ignored. Consider that 76 percent of job seekers deem workplace diversity as an important factor in their decision process. Further, there is extensive research that greater

diversity and representation equals higher performing teams. States have made good progress on modernizing by offering workplace flexibility, remote/hybrid work, reskilling and eliminating four-year degree requirements where possible. It is imperative that CIOs promote data and fact-based methods of recruiting and retaining to have the most qualified staff for the current and next generation state CIO office.

Identity and Access Management

Identity and access management (IAM) has remained a priority for state government as demonstrated in NASCIO’s Top Ten priorities list in the past several years, including 2024 where it sits at priority eight. IAM is inherent in other priorities such as cybersecurity, digital government services and customer relationship management. However, IAM has been an ongoing challenge for state government as it works toward delivering a positive citizen experience, continuing to fight fraud and abuse of state government services and moves toward an enterprise-wide view of our citizens. That enterprise view requires individual agencies to be a coordinated, collaborative cohort of service providers that not only delivers their specific services under their immediate purview but to also understand and value the similar responsibilities of all other state agencies. In the end, citizens benefit when they can come in any state government door and know they will be informed about what services are available and be enabled to reach those services. As one CIO told us, “Good IAM is the gateway to good digital government.”

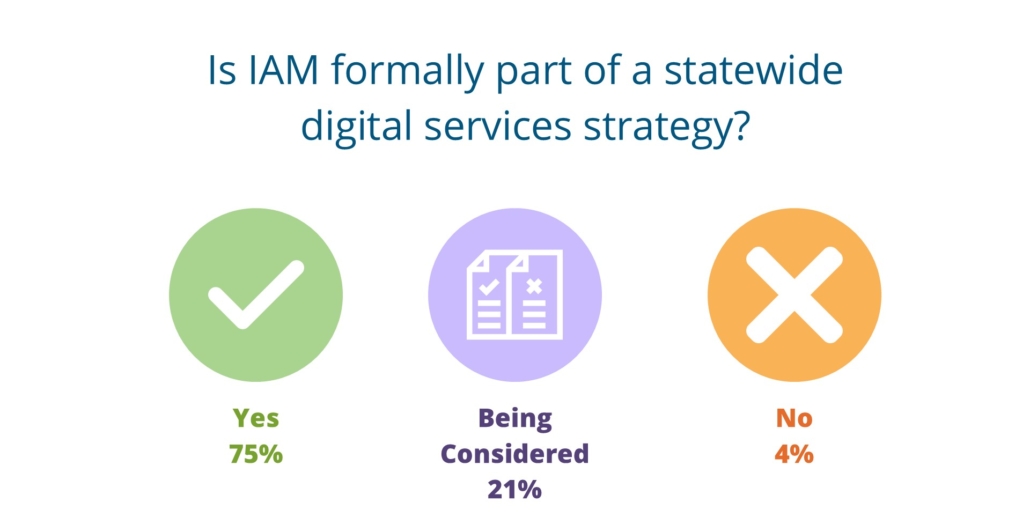

We asked CIOs about IAM integrating into their statewide digital services strategy and an overwhelming majority (74 percent) said yes. Only four percent said no and 21 percent report it is being considered.

We assume that states considering integrating IAM into their statewide digital services strategy are still in the thick of exploring and researching. Ideally this means they are assessing the methods, disciplines and journey maps necessary for pursuing an enterprise-wide digital identity strategy, as well as exploring ways to operationalize that strategy effectively.

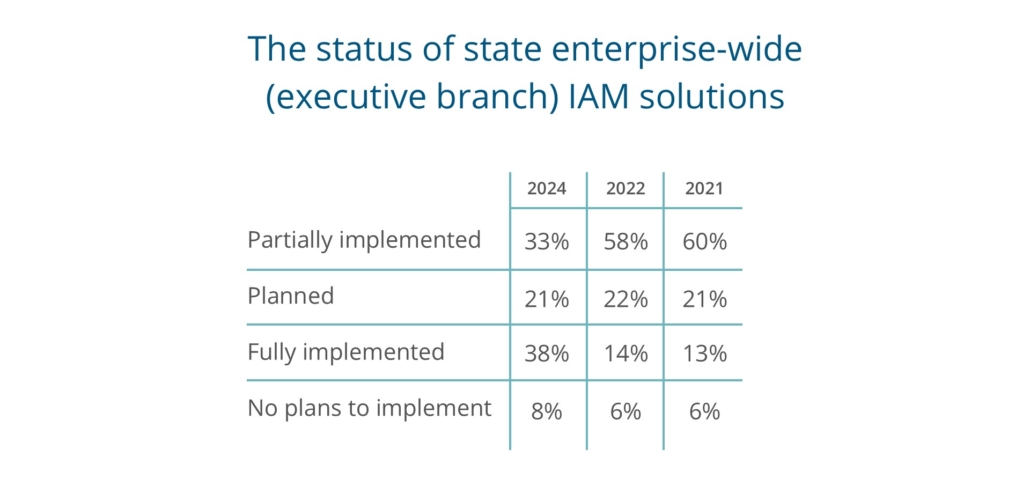

Next, we asked CIOs to characterize the status of their enterprise-wide IAM solution, a question that we have also asked in previous state CIO surveys. Here again, the majority of responding state CIOs are pursuing an enterprise-wide vision for identity and access management.

We expect enterprise-wide approaches will mature going forward as IAM strategy and operations will be a dynamic capability getting better and better as new business and technology enabling capabilities arrive.

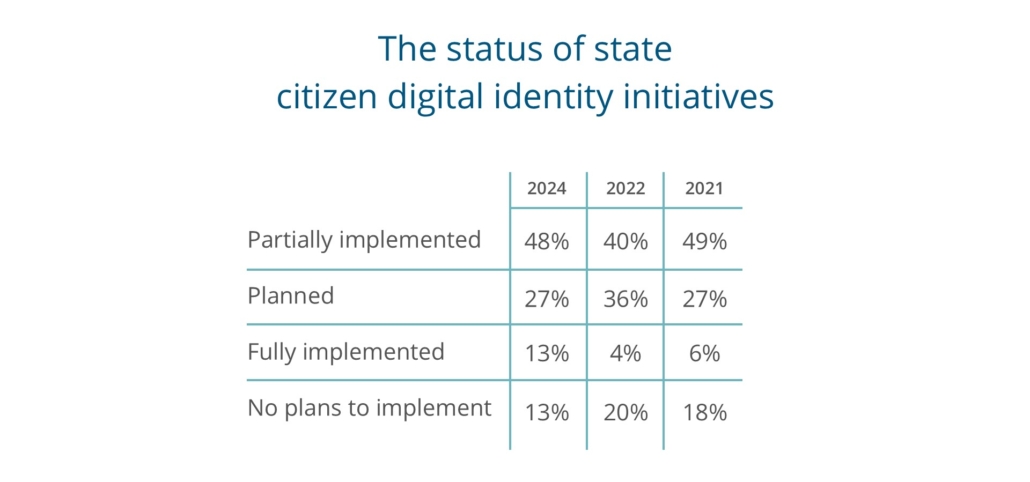

We also asked CIOs to characterize the status of their external or citizen digital identity initiative. From these trends we see that states have made some progress in establishing digital identities for citizens with those who have fully implemented their initiatives steadily increasing since 2021. And there has been a reduction in the number of states that have no plans to implement such a strategy.

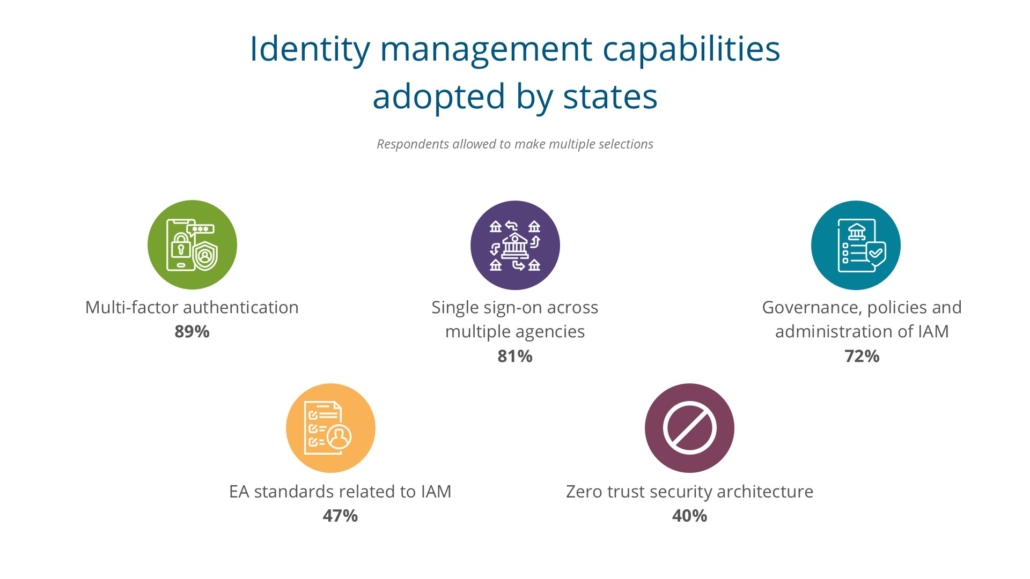

We also wanted to know which specific IAM capabilities states have adopted and, not surprisingly, MFA (multi-factor authentication), has been adopted by 89 percent of states. Other top responses include single sign-on across multiple applications (81%), and the establishment of IAM governance and policies (70%).

We next asked an open-ended question of our state CIOs regarding their authority for establishing an enterprise-wide IAM solution. There is a wide range of responses from “mandated” to “none” and everything in between as relayed by this comment: “That is a hotly debated topic!” But the majority of

CIOs report that they have clear authority for establishing an enterprise-wide IAM solution.

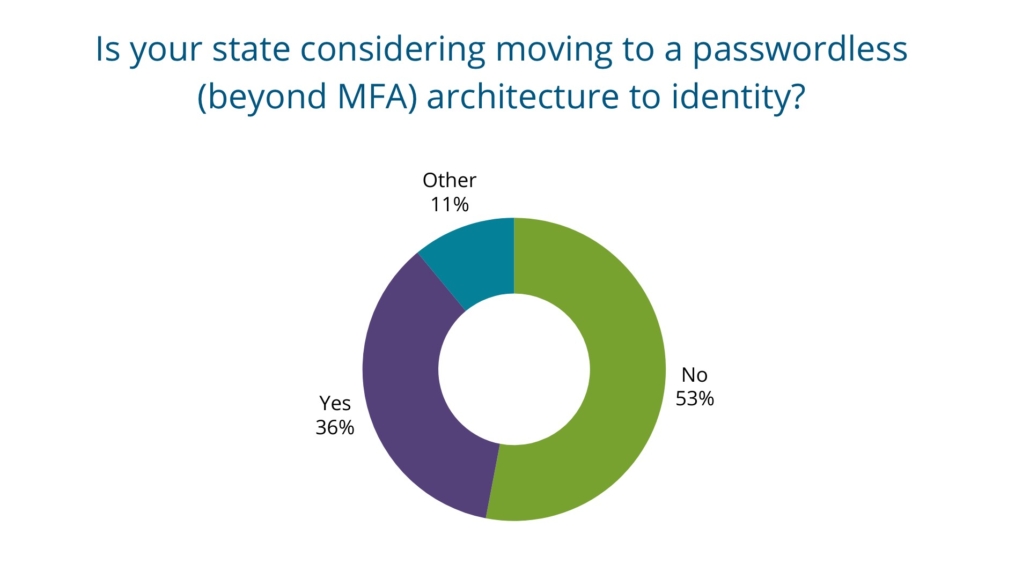

We also asked state CIOs if they are considering passwordless architectures for enabling IAM. Thirty-six percent are, while 53 percent are not. As states continue in their IAM and MFA journeys, we expect that more will consider a passwordless architecture in the future.

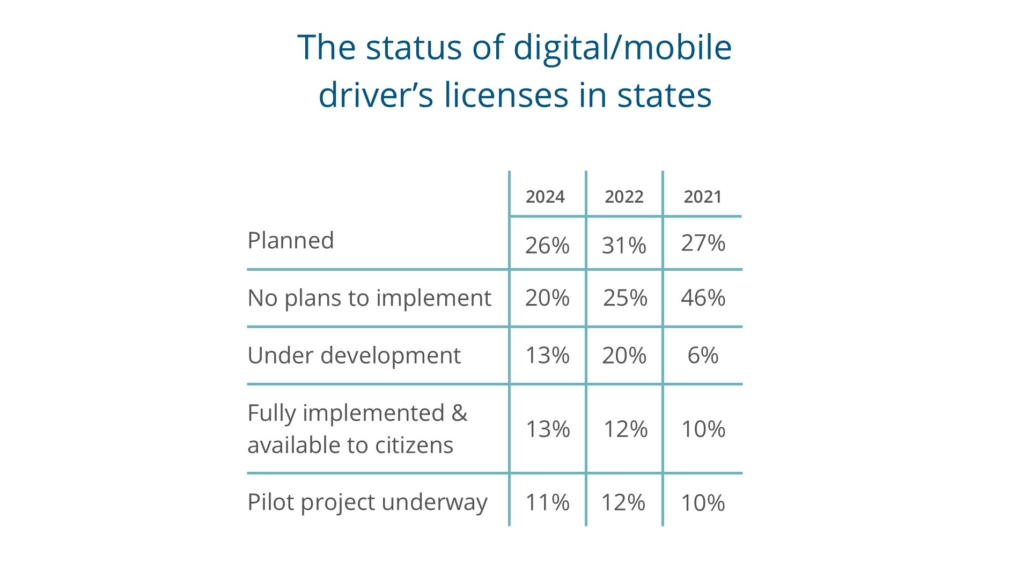

Finally in this section, we asked state CIOs about the status of their digital/mobile driver’s license initiatives and below we compare with the results from the first time we asked this question in 2021 and when we last asked in 2022. Progress has been made toward implementing this capability as can be seen

in the significant reduction in state CIOs responses of no plans to implement.

This year we also added a response option that we hadn’t in previous years and seven percent of states indicate their mobile driver’s licenses are now accepted by federal agencies and third-party organizations. We anticipate that this is the next major step in states’ mobile driver’s license journey.

Federal Cybersecurity Funding

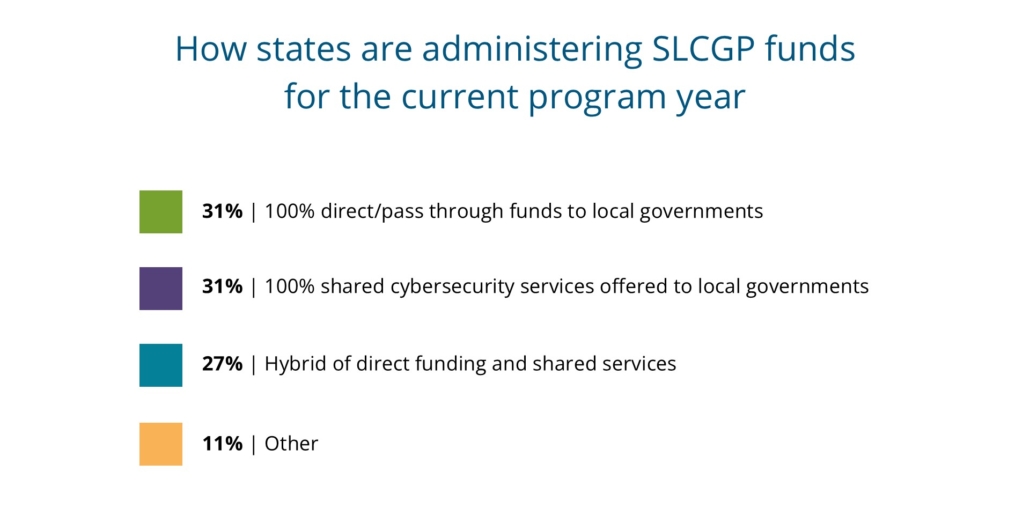

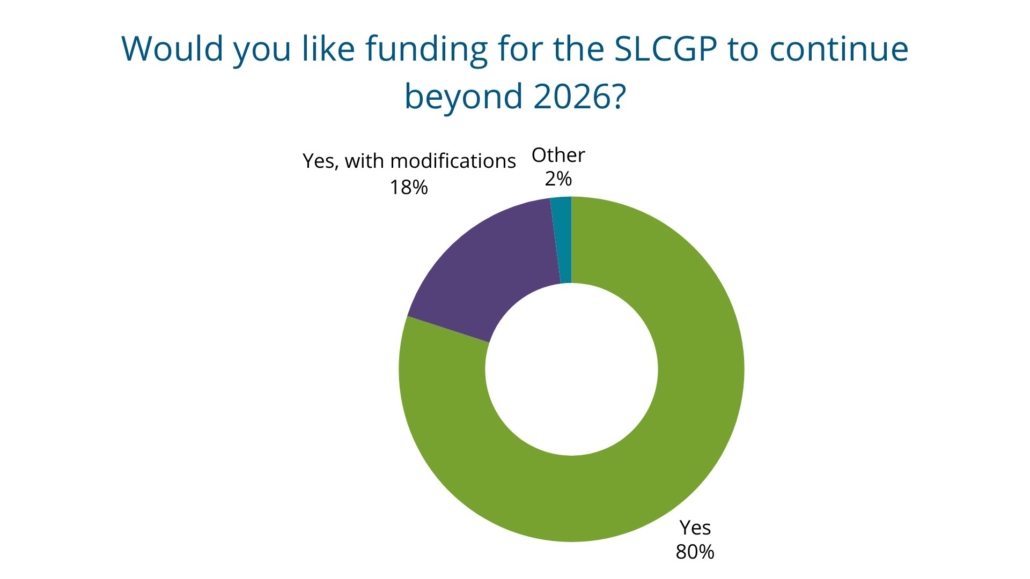

Federal funding to support cybersecurity activities continues to be a major priority for respondents, and the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program (SLCSGP) has been a key avenue for states who wish to leverage these funds for cybersecurity improvements. As the program enters its third year, states

are fairly evenly split in how they are directing SLCGP resources with one-third choosing 100 percent passthrough, one-third choosing 100 percent shared services and the last third taking a hybrid approach. This is different from the first year of the program where very few states took a 100 percent passthrough/direct funding approach.

Whether a state has opted to provide funds directly to local governments, offer shared services to local governments or deliver a hybrid approach has been dependent upon a state’s governance structure, the needs of its communities, the availability of certain service offerings and other diverse factors. One respondent said that “We are implementing (or trying to) a whole-of-state approach, recognizing that our weakest links often need the most support, particularly those under-funded entities that regularly deal with highly sensitive data.” While many states have embraced a whole-of-state approach to cybersecurity to some degree, the flexibility to tailor SLCGP plans to the needs and goals of each state has been a key to its success so far.

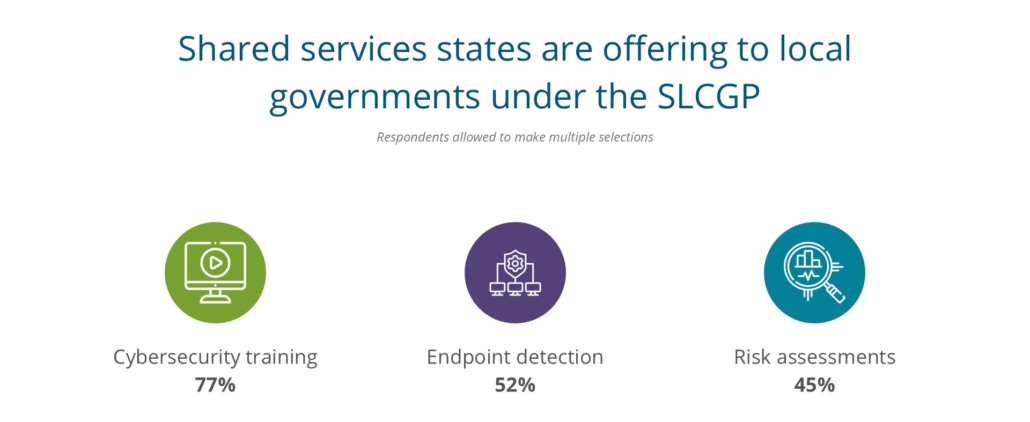

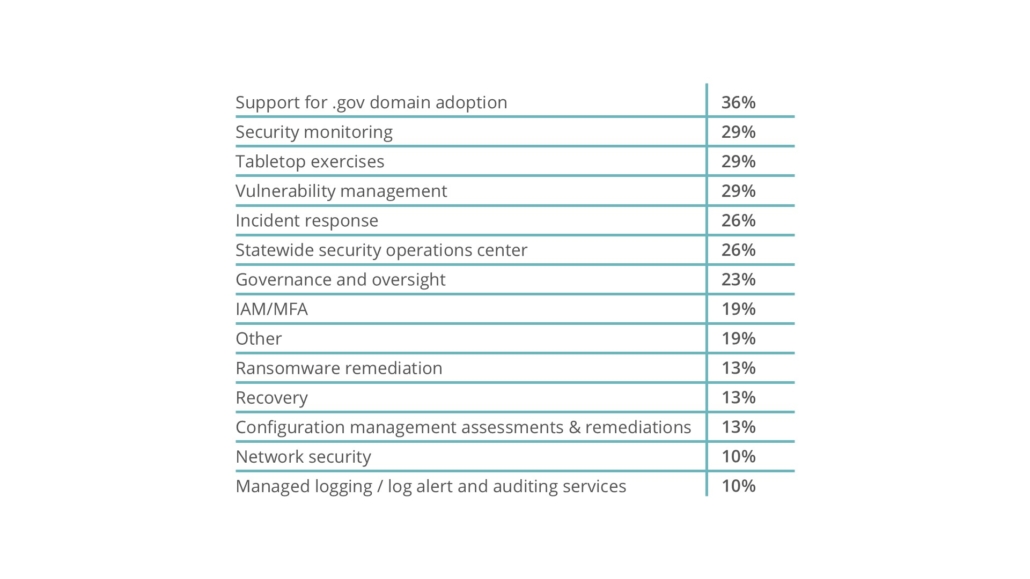

When it comes to how states are using the money to address cybersecurity needs, responses also reflect the areas where states are working to address vulnerabilities and other shortages. It should be noted that while the state CIO is not the sole voice for determining how SLCGP funds will be used, they typically have substantial input into their direction.

The high percentage being directed to cybersecurity training reflects the great need that exists to educate employees at the state and local level on cybersecurity. According to one respondent: “Our statewide program has been widely embraced and we have provided training and end point protection to over 20,000 people in local roles (city and county).” Other top categories of services offered to local governments includes endpoint detection, risk assessments, support for .gov domain adoption (a perennial NASCIO advocacy priority) and security monitoring.

While more can be done to improve the efficacy of SLCGP, it has already yielded encouraging results for states and almost all respondents stated that it should be extended beyond 2026 (though some had conditions or suggested changes to accompany any extensions). One respondent called it an “excellent program that is closing gaps with local governments, tribes, and education” and another stated that “continued funding is critical to maintain rate of progress.”

This year NASCIO also asked whether respondents would support a federal cybersecurity grant program that is targeted only to state government. Overall, states were enthusiastic in supporting such a program, if that program didn’t jeopardize the whole-of-state approach to cybersecurity or come at the expense of support for local governments. One CIO said that the greatest concern in the state is “for our municipalities – we need to account for their concerns and help build them up to be prepared.” Another expressed that while a state specific program “would be very valuable, it is essential to support all local forms of government.”

Multiple respondents also stated that while grant programs are helpful, long-term, dedicated funds that do not require increasing matches from the state are a more comprehensive and effective solution than the current SLCGP model.

From this data it is clear that states welcome cybersecurity funding assistance from the federal government. However, there is room for improvement in how grants are administered in the future. There is a growing recognition at all levels of government that cybersecurity is no longer an IT issue; it is a business risk that impacts the daily functioning of our society and economy, as well as a potential threat to our nation’s security.

Conclusion

So, where do we see things going from here? The big themes like more GenAI, increased consolidation and centralization, the need for strong foundational blocks like EA, disaster recovery, acquisition and IAM will continue and expand as the demand for digital services will continue to increase. But how will any of this happen if states don’t have the technology workforce that they so very much need? In short, it likely won’t. States will have to modernize their work environment and policies to attract their own workforce or outsource these critical roles. As we stated in the introduction, it is clear to us that focusing on these issues will lay the groundwork for the next generation of state CIO offices in 2025 and beyond.

States Participating in the Survey

State of Alabama, Daniel Urquhart, Secretary of Information Technology

State of Alaska, Bill Smith, Chief Information Officer

State of Arizona, J.R. Sloan, State Chief Information Officer

State of Arkansas, Jay Harton, Interim Director and Chief Technology Officer

State of California, Liana Bailey-Crimmins, Chief Information Officer and Director

State of Colorado, David Edinger, State Chief Information Officer and OIT Executive Director

State of Connecticut, Mark Raymond, Chief Information Officer

State of Delaware, Gregory Lane, Chief Information Officer

State of Florida, Leo Schoonover, State Chief Technology Officer

State of Georgia, Shawnzia Thomas, State Chief Information Officer and GTA Executive Director

State of Hawai’i, Doug Murdock, Former Chief Information Officer

State of Idaho, Alberto Gonzalez, Chief Information Officer

State of Illinois, Sanjay Gupta, Secretary and State Chief Information Officer

State of Indiana, Tracy Barnes, State Chief Information Officer

State of Iowa, Matt Behrens, Chief Information Officer

State of Kansas, Jeff Maxon, Chief Information Technology Officer

Commonwealth of Kentucky, Ruth Day, Chief Information Officer

State of Louisiana, Derek Williams

State of Maine, Nicholas Marquis, Acting Chief Information Officer

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Jason Snyder, Secretary and Chief Information Officer

State of Michigan, Laura Clark, Chief Information Officer

State of Minnesota, Tarek Tomes, Commissioner and Chief Information Officer

State of Mississippi, David Johnson, Former Chief Information Officer

State of Missouri, John Laurent, Acting Chief Information Officer

State of Montana, Kevin Gilbertson, Chief Information Officer

State of Nevada, Timothy Galluzi, State Chief Information Officer

State of New Hampshire, Denis Goulet, Commissioner / Chief Information Officer

State of New Jersey, Christopher Rein, Chief Technology Officer

State of New Mexico, Raja Sambandam, Acting Cabinet Secretary and State Chief Information Officer

State of New York, Dru Rai, State Chief Information Officer and Director

State of North Carolina, James Weaver, Secretary and State Chief Information Officer

State of North Dakota, Greg Hoffman, Chief Information Officer

State of Ohio, Katrina Flory, State Chief Information Officer / Assistant Director

State of Oklahoma, Joe McIntosh, State Chief Information Officer

State of Oregon, Terrence Woods, Chief Information Officer

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Amaya Capellan, Chief Information Officer and Deputy Secretary for Information Technology

State of Rhode Island, Brian Tardiff, Chief Digital Officer and Chief Information Officer

State of South Carolina, Nathan Hogue, Chief Information Officer

State of South Dakota, Jeff Clines, Former State Chief Information Officer

State of Tennessee, Stephanie Dedmon, State Chief Information Officer

State of Texas, Amanda Crawford, Executive Director and State Chief Information Officer

State of Utah, Alan Fuller, Chief Information Officer

State of Vermont, Denise Reilly-Hughes, Secretary

U.S. Virgin Islands, Rupert Ross, Director and Chief Information Officer

Commonwealth of Virginia, Robert Osmond, State Chief Information Officer

State of Washington, William Kehoe, Director and State Chief Information Officer

State of West Virginia, Heather Abbott, Chief Information Officer

State of Wisconsin, Trina Zanow, Chief Information Officer

State of Wyoming, Aaron Roberts, Former Interim Chief Information Officer

Authors and Contributors

Amy Glasscock, CIPM, Program Director, Innovation and Emerging Issues

Emily Lane, CAE, Director of Experience and Engagement

Eric Sweden, MSIH, MBA, CGCIO, Program Director, Enterprise Architecture and Governance

Alex Whitaker, Director of Government Affairs

Kalea Young-Gibson, Policy Analyst